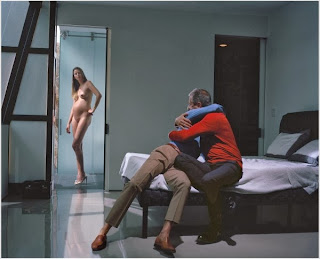

Iolanda, 2011 ©Philip-Lorca diCorcia

Working in the space between documentary and staged

photography, Philip-Lorca diCorcia recently exhibited a new series in London, ‘East of Eden’, at

David Zwirner in London. The title alludes to John Steinbeck’s epic novel published in 1952 and biblical parables found in the

Book of Genesis such as Cain and Abel. While explaining how the project

originated and evolved, Philip-Lorca comments on the Bush Presidency, the economic crisis and the state of art photography today.

JW: How did ‘East of Eden’ emerge and develop as your latest

project?

PL dC: It started as a reaction to the economic bubble that

burst and people’s conception of the world and the possibilities that had once existed.

JW: The gallery’s press release refers to impact of the Bush

presidency.

‘East of Eden’ refers to the end of the Bush presidency and the

wars that were futile and misconceived, the economic situation and the stock

market being at an all time high, everyone leveraging themselves to death and

mortgages being given away. All of that. There was a sense of delusion in the

whole thing and knowledge came with the collapse of everything. The apple in

Adam and Eve represented knowledge. They call it the Fall and the expulsion. The

president had lied to you and all these people had lied. I felt that there was

a certain analogy that serves as a jumping off point and obliquely refers to the

shocking change that followed.

JW: This underlying political sense of the time we’re living

in is not necessarily explicit in scenes of an ordinary house such as ‘Mount

Ararat, Pennsylvania’.

PL dC: I was attracted to the scene because it happened to

have that name but there you have some windmills and it’s in an area of Pennsylvania

where they do fracking, which is very contentious. I ended up with the opposite

of fracking. If you take out the windmills, this picture wouldn’t be there. It’s

like the invasion of technology, ‘The War of the Worlds’. It must look

extremely American to a British audience – the American flag and the lack of

people. I’ve been involved in a bunch of Edward Hopper projects before. There are hardly any of my pictures before that

don’t have people in them. This architecture epitomises middle class of America,

which everyone talks about, but I’m not sure who they actually are.

JW: Was this a new turn or interest?

PL dC: No, there’s an implicit event in the photograph. One

of the things that I always like about Edward Hopper is almost about what you

don’t see. Something may happen before or after. I was trying to create the

same effect in some of the other pictures like Stockton, California’ with the

scorched fence. One is on the East coast and one is on the West Coast. At the

time I didn’t know it, but it was the first town to go bankrupt, but I didn’t

know that at the time. There was one thing that really bothered me and I

couldn’t deal with it so I put in this huge piece of concrete. It’s not very

much.

JW: So you do allow yourself some licence to manipulate the

image with digital processes?

PL dC: Some of these photographs are made with view cameras

so at first you see an upside down image within a grid. You can move things up

and down. I have never taken a picture just holding a camera. I never just take

a picture holding a camera. I always put a camera on a tripod. I combine it

with using a Polaroid for preparation so I know where everything is. Sometimes

I can’t know how to resolve it. I’m stuck against the wall. I don’t have a

hundred million lenses like a Zoom. In the past a view camera was used to

correct perspective. I use a level on top of the camera so it’s level front to

back, right to left. These lines are all parallel to the picture plane.

JW: So there’s an aesthetic judgement involved when you’re composing,

processing and editing the picture?

PL dC: I’ve always been a person who uses the environment to

reflect the psychological and narrative content. I remember photographing my

series, ‘Hustlers’. I’d give the sitters a Polaroid once in a while and I might

see them later on the street and someone would ask ‘is this guy alright?’ and

he’d reply that I’d taken their picture earlier and pull out the polaroid and

he’d cut his head out. The rest of the picture was irrelevant.

JW: When you were making this new series were you conscious

of thematic links?

PL dC: It was a five-year project and I did look for

specific things. I looked for fires, not necessarily as a reflection of some

apocalypse, but yes.

JW: There seems to be an underlying tension or anxiety in

some of the photos. Some of which you appear to stage and some of which seem incidental

like the fallen gravestone in ‘After The Fall’.

PL dC: You can’t read

any of the names on the tombstones. Some of the gravestones are blurred so you

can’t see anyone’s name. It was taken after a hurricane, which knocked down the

tree. I didn’t go looking for this, though I had my camera. My father is buried

there and I hadn’t been back since his funeral in 1980. I don’t really

understand this one to tell the truth. There’s something about the logs…the

light was clearly dramatized by the time of day and the season.

JW: There are two works connected by sight and blindness,

‘Andrea’ and ‘Lynn and Shirley’

PL dC: It started out

when I was told that blind people can’t dream. They don’t have any narrative

because they don’t have an image bank. Andrea doesn’t have the possibility of

seeing colour or light because she was born without an optic nerve. I don’t

know what Lynn and Shirley meant to me, Adam and Eve, white and black. They

weren’t born blind. I connect these things very loosely. He was shot in the

head and she has macular degeneration.

JW: Did you have to win their trust? Is that how you work?

I visited Andrea. My sister teaches special education and

her colleague has two blind kids with the same condition. I thought of Andrea

as the anti-Eve. Today everyone would accept that Eve would be a fashion model

like the pregnant model in ‘Cain and Abel’.

JW: Does Cain and Abel bear any relationship to surrogacy?

It seems to possess the richest possibility for narrative in the exhibition.

PL dC: I threw everything at this image. This was the last

one I made and I really went for it. The guys on the bed don’t know her and I

don’t normally photograph naked women. I do a few things that I don’t normally

do like take the belly button out. Eve didn’t have one because she was born

from a rib. It’s Cain and Abel but actually a gay couple. I meant it to be

ambiguous. You don’t know if they’re fighting or hugging but I didn’t succeed

because everyone thinks they are embracing. They were quite shy of the camera.

It was quite a difficult shoot. The space wasn’t very big enough and a bit too

much with the ‘mod cons’, but it had dramatic like elements like the floor being

so reflective and the pregnant model wasn’t shy. ‘The Hamptons’ is named after

the fashionable area of Long Island outside New York and has a humorous quality

with two dogs watching television inside a living room This is the most popular

picture. There’s nothing depressing about it. It was taken in the Hamptons and

represents to me the character of the place. It’s actually taken in the home of

the person who publishes my books, Pascal Dangin, who made the prints in the

show.

Cain and Abel, ©Philip-Lorca diCorcia

JW: Sometimes you’ll invite fiends and family to model in

the photos. Can you explain how that happened in ‘Iolanda’?

PL dC: The model is my mother-in-law. I was given a

commission to do anything I wanted for the 75th anniversary of Coach,

the handbag company. ‘Iolanda’ was taken in a hotel where the rooms cost $600

to $900 dollars a night. So I did other pictures in the room with other models.

To cover my ass, I put a handbag in shot and I forgot to digitally remove it. I

was too busy trying to add a tornado on the television screen. The picture is

made a success by her reflected face being distorted by the passing ferry.

These things are manipulated. You would never have seen her face in glass without

digital alteration though I still don’t use a digital camera. When I first

started working in fashion photography I made an effort to hide the lights and

someone said ‘you can take them out

later’! I don’t like the way that digital images look. The Hustlers series in

New York are made by scanning and manipulating my old negatives on a computer

and then printing from the resulting 8 by 10 negative to produce a C-type

print.

JW: I’m struck how ‘Abraham’ shows a younger person being

put on the defensive. Is this connected to recent wars? It’s quite threatening

with the dart flying at the teenager’s face and he seems genuinely startled.

PL dC: He was. He’s going to try to stick his hands up. That’s

my son and that’s my hand. People remark that we have the same hands. I really

was throwing a dart at him. I put gaffer tape on the tip so it wouldn’t

puncture him!

JW So these photographs emerge out of a whole variety of

ideas and experiences? You don’t seem to have a particular strategy that you

stick to.

PL dC: I thought of ‘Epiphany’, the pole dancer, as Lilith

or the snake slithering down the tree. I went specifically out to LA and I had

a connection to find this woman who I had seen before. She’s suspending herself

from the mirrored ceiling, which is very difficult to do. Lilith, Adam’s first

wife in Jewish folklore, is sometimes described as a snake. Unfortunately for this

series, ‘East of Eden’, most people think the image is connected to an earlier

series I made of pole dancers but those earlier photographs have no context.

JW: ‘Sylmar, California’ uses a particular Californian light

to create a Reaganesque image of a cowboy on a horse. It has that mythic

quality of settling the west taken against a tragic, burnt landscape.

PL dC: The landscape is very barren after a fire but the trees

are not black and are still green. There’s a lot of beauty in tragedy. That’s

the thing about California, it’s constantly on fire. In ‘Lacy’, the model asked

me what I wanted her to wear so I looked at what she had and realised that the

place was charred like that, I chose a dress with flowers. I guess she has a nostalgic

look and she also happens to be a pole dancer.

JW: How do you now view the Hustler series made in Los

Angeles over 20 years ago and recently exhibited at David Zwirner in New York?

PL dC: It’s one of my first and favourites series. It took

place during that AIDs period. I happened to know a lot of people who died

including my brother. I was fed up with ‘hip’ New York. I was never actually

that ‘hip’ although I was playing in a band. Twenty years later there has been

a homogenisation of culture. People are very cynically using youth brands or street

styles and in a year turn them into something you see in every city of the

world. Take Supreme the brand, for example, which used to be a skateboard

company.

JW You’ve just had a big exhibition at the Schirn Kunsthalle

in Frankfurt. What was your experience of mounting a large retrospective?

PL dC: Back off from the word ‘retrospective’. It did not

include significant projects that I’ve done. Because of the nature of museums

and money now they more or less have to borrow everything. They are not going

to produce the work for the show. So what they can put in the show is

determined by what they can borrow. If I were to call something a

‘retrospective’, I would say it has to be inclusive and selecting the images

that they want rather than what they can get. I would call that exhibition in Frankfurt

a ‘survey’. It’s moving onto the De Pont in the Netherlands and then to the

Hepworth Gallery in Yorkshire.

JW: So are there some challenges with putting on a museum

show?

PL dC: It’s not that I produce so much work but in terms of

square footage there are things, for instance, the ‘Storybook Life’ shown at

the Whitechapel Gallery in 2003 as one work. It’ s the whole thing, not a

single image, which takes up a lot of installation space. In the case of the De

Pont in the Netherlands they decided to do a thousand images running 351 feet

in one long row. It was first shown as a single line at David Werner, in New

York, they exhibited the series laid out in a spiral. It was clearly laid out

and people really did move in the order they were shown. That was the most

successful iteration.

JW: D you think Photography is being determined by fashion?

PL dC: I don’t know. Photography

has lost some of its lustre in the art world. People want unique objects. I

don’t think it’s a coincidence that when photography started to be less

prevalent, it became exceptionally abstract or extremely conceptual. The work

people want on their walls…. I’ll just say it, it’s decorating. There are all

sorts of art markets. There is the one where people actually live with art and

then there’s the one where it goes straight to the warehouse. If it goes

straight to the warehouse, they are speculating. And the auction market for photography,

unless you’re Andreas Gursky, has not been favourable.

JW: But you remain committed to photography.

PL dC: I’m not going

to change. It gets me out of the house. I could never go to a studio and dream

up something because it would be irrelevant to me.

JW: What have you learnt by exhibiting this project?

PL dC: There are two

interesting questions people have asked me about the exhibition. Now that the

crisis is supposedly over, do you think the work has changed its significance

or meaning? The answer is simple – I don’t think the crisis is over. The other question

is ‘as there are no titles on the wall do you think it’ s unfair that people

have to figure out so much, even the connection of these images to the novel ‘East

of Eden’ which can be completely lost. I guess my answer to that is that it’s

not lost if you live with it. If you experience everything by taking a twenty-minute

tour of an art gallery or leafing through a magazine then the point is going to

be lost on you. My ambition has been to get beyond that. This comes partly from

working for magazines and realising that people don’t even look at the damned

images unless they’re naked.

JW: So the images have to be self-sufficient?

These images are not meant to be seen just in conjunction

with each other and are independent of their titles. My project ‘A Storybook Life’

has no information or foreword, just the location and the date at the end of

the book. In a question and answer session at Whitechapel Gallery people seemed

almost angry that I wouldn’t supply them with that kind of anecdotal

information, something to say that’s my brother or this happened. People really

want that from photography. They want the Nan Goldin experience, 'this is my

world' – or a cool lifestyle. ‘I’m Wolfgang Tillman and I don’t live like you

do.’ People are attracted to that because photography has traditionally served

as a document of events in your life.